Bower Bird

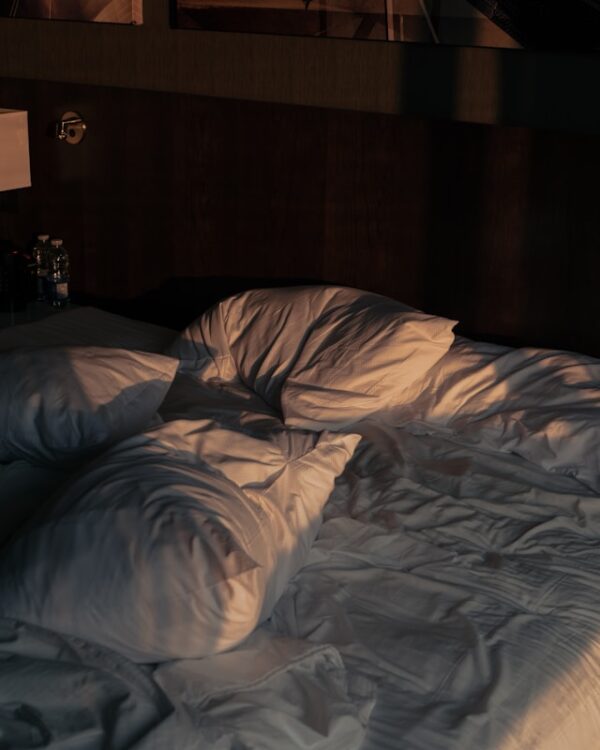

STELLA LEFT MY BED when the first pale hint of light appeared in the window. Whenever she stopped by on her way to somewhere, we lingered the morning away in our fetal curve, savoring the early light and the breeze drifting in above the headboard. A cozy blanket of fog or the shape and color of high-gliding clouds might demand her attention. Lying there with her, sometimes quiet, sometimes chattering about dreams or the day to come was more satisfying than a meal so filling I could skip the next one. But this morning we cuddled for the shortest time before she left to walk in the woods in search of forest edibles for our next meal and then to visit people expecting bits of her attention.

Other times she would not return until a dinner I would make and serve with candles and flowers and thick slabs of butter she loved to slather over the fine bread she had picked up on the way. Or she might call to ask did I want to take an afternoon walk or a nap? Or we would make a plan for the weekend, and she would keep it. But on this morning she grabbed her clothes from the railing over the open stairs and descended without the languor that told me she would return for us to lie entwined like dreamy young lovers.

“The bower,” I said aloud. That is what she named my bedroom after I converted the attic room’s drop-down ladder into a broad set of stairs and did everything I could to beautify the space. I had not known how much of my motivation to fix it up was about her until she showed me. After she did, bower was the only thing I could call it.

“Jimmers, you are my bower bird,” she had said on the phone a month before when she thought she might come through town to see my remodeled space on her way to visit whomever. She loved my adornments: the Persian rug, the peace lily in a big pot in front of the dormer window, the paintings and photographs unpacked from neglected boxes, the forged hooks for her wreaths and the birds she made of fine wire, the cozy corner chair on which she had placed a seat cover she had woven from strips of my old tee shirts on her special loom. It seemed that she might stick around and maybe even make it our home.

“Your bower bird?” I had asked. “What, pray tell, is a bower bird?”

“Ohhh,” Stella sighed. “The male builds a little house to attract a mate. He makes a little avenue leading to it like your path of roses, and walls of woven twigs and leaves and grass with an opening and sometimes a roof. He fills it with decorations. Flowers and feathers, shells and stones, even discarded trash, so long as it’s colorful. Bower birds are little recyclers, and their choice of colors is said to match their preference for mates. So, you are my bower bird.”

“How is the match so far?” I asked her.

“I love to visit,” she said. “I love to bring you flowers for your bower. Or things I make from recycled things. Oh, I think I’ll bring you heart stones I find along the river or in the water. You can go with me. We will find them together. For your bower.”

I remember the little tiff we had. I had asked her to stay longer. It spoiled a forest walk to collect edible greens she finds on the forest floor and her favorite, barbed nettles that lose their spikes and bitterness when she sautées them with onions. But my request displeased her. She didn’t stay with me that night or say when she would return.

The next afternoon I came home to find, at the foot of my front door, a perfectly shaped heart of rose petals three feet high and across, filled in with the dropped petals from my roses, and Stella napping in my bower. She knows where I hide the key. I knew then that she would often return but never stay.

This morning the kiss she brushed on my cheek before she rose sufficed, for in the few moments we shared before she left, we planned her return. So I closed my eyes and concentrated on her sounds through the open stairwell: water turning on and off, a gurgle, a brush coursing through her thick, flowing mane, a bottle clinking on the counter, the thump of sandals as she left.

This is enough, I thought. This is good. Don’t ask for more.

But I knew I would.

I laid my hand on the place Stella lay minutes before. It was still warm. I imagined her smiling like a child safe in the uncomplicated world of the senses. From the laugh in her voice and the way she skipped and swung her arms in great circles on our wood walks, from the scent and feel of her skin when we showered and her coos of pleasure at the smells of a meal she was preparing or one of mine waiting under her nose, from the ways I had found to touch her with a freedom that arose more from my delight in her skin and flesh than the lusty pinnacle of sex, I knew this to be true. I could touch Stella like that for hours.

And I did. And she loved it. She told me she went to a far-off place and wanted to remain there forever. I loved sending her there from our bed in our bower – my bower – where she wanted me to tell stories. Where more and more I wanted her to stay. I thought my stories might keep her.

“Tell me another,” she had said the night before, her face golden under the glow of my candles. Her feet were in my hands, my face at her feet, an arrangement that could last as long as I wanted. I was in awe of its intimacy. When I looked at her toes, touched them, kissed them, held them in my mouth, I thought I was touching her naked soul. In my rapture I believed I might not need more of her time and found myself wanting to guard her solitude, even her soul, from my intrusions. To protect another’s soul, you must love her privacy, for that is where she finds her necessary repose. I decided Stella needed that rest more than she needed me, and thought I had accepted this. More than ever, I understood that you must love what your lover needs, especially the parts you wish she didn’t. You must treasure it and never ask her to give it up.

Or much of it anyway. I always carried a nagging doubt as a cautionary note, a ballast against my feet flying too far off solid ground. Eventually I would have to negotiate a few conditions. Until then or perhaps forever, I would push them aside and try not to hope for what I really wanted.

“Please tell me a story,” she said again.

“I can’t right now,” I answered. “I’m in the middle of a great one.”

“Jimmers, come on! Tell me a story!”

“Okay. I have one, but it’s sad. This is not a time for sad.”

“If the one that came up is sad,” she said, “that’s the one to tell. Or tell me about an old lover. I love to hear about your lovers.”

“Let’s do a trade then,” I said. “Lover for lover.”

“You first, Jimmers.”

“Okay, here’s one about making love in the woods.”

“Ohhh my,” she said. “I’m all ears. When you are done, I want you inside me.”

“That’s not a story.”

“It will be.”

I laid my palm on the space that had held Stella. Cool now, it was time to leave my musings behind and begin the things that needed doing, knowing that at least this one day held the promise of Stella’s return.

I waited for the click of the front door closing. I had forgotten she was already gone.

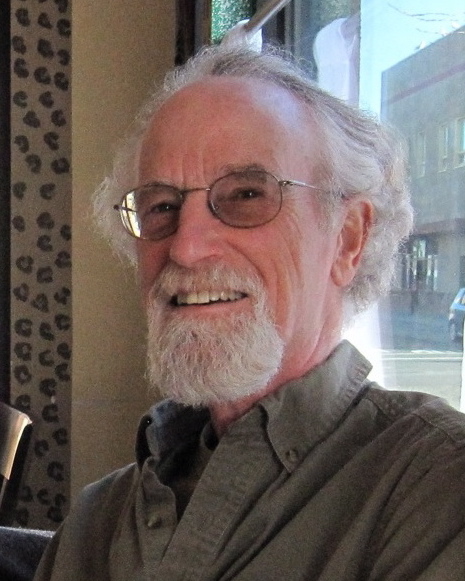

For the last thirty years, Jim has mined his experience as a family man, public legal services attorney,

language arts teacher, blacksmith, community college instructor of criminal justice and paralegal

training, basic law enforcement training director, and, finally, twenty years as a mediator helping

couples get through divorce in a collaborative manner. He writes stories about the challenges of

family, love, and work. Eleven of his short stories have been published in literary journals. He has

self-published one novel, Boundaries, and two short story collections, Filling Up in Cumby and Last

Night at The Vista Cafe.

Jim will soon be looking for a home for a two-book novel series: Third Floor and Redemption, the

story of Rachel and Joseph Singer, twin brother and sister struggling with very difficult family

circumstances.